There has never been an arena built in Memphis with the same quality, acoustics, care, and comfort as the Mid-South Coliseum.

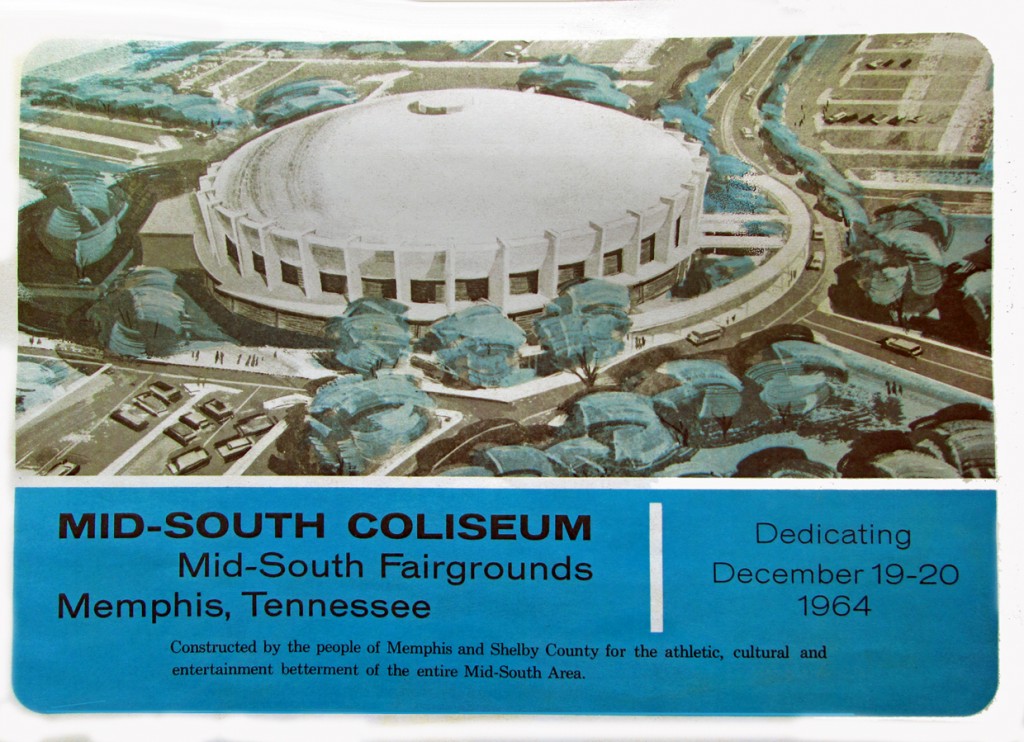

It was the culmination of a dream that had begun in the late 1950s for a new, all-purpose, “blue chip” public arena, and when the doors were thrown open in 1964, the building produced a burst of civic pride (building on the momentum created by the opening of the Roy Harrover-designed Memphis International Airport a year earlier) not seen again until the opening of AutoZone Park and FedExForum about four decades later.

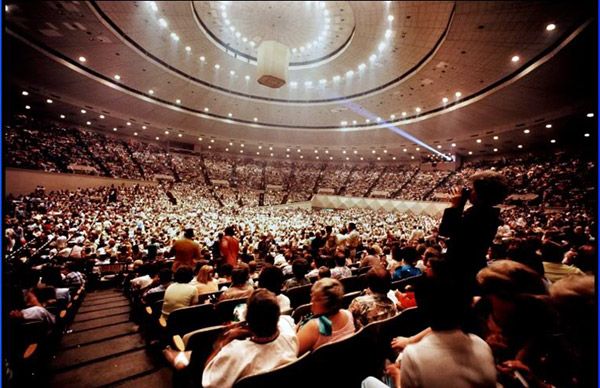

Anyone who bought a ticket for an event in the Coliseum’s opening year remembers the terrazzo, the brick, the glazed ceramic tiles, the symmetry, easy access, lack of obstructions, and its overall comfort. It was impossible to imagine that another arena in the South could compete with it.

Although the building was similar to the coliseums opened in 1960 in Jacksonville and in Mobile in 1965, it was markedly different in one respect: it was not planned as a segregated facility. Considering that Henry Loeb was serving his first term as mayor, and would later be immortalized for the infamous resistance to the unionization of Memphis’ sanitation workers which brought Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to the city, it is a historical irony that plans for the building were developed by the Loeb Administration and apparently always envisioned integrated audiences.

The Early Years

Multiple locations were evaluated by city-county planners for the Coliseum, including some outside Memphis, but in the end, the Fairgrounds was selected. City of Memphis and Shelby County, respectively paying 60% and 40% of the costs, selected Merrill G. Ehrman of Furbringer and Ehrman as lead architect with support from Robert Lee Hall & Associates. Before they began architectural drawings, they toured recently built coliseum arenas, and when these visits were concluded, they proposed a coliseum structure whose cost would ultimately be $4.7 million ($36.5 million in today’s money)

The Coliseum’s first event in October, 1964, was the Ringling Brothers Circus, and it was followed by its first stage show, the WDIA Goodwill Revue, which also was its first sell-out and set an attendance record that stood for years. In its 42-year history, the Coliseum was the go-to place for legendary concerts and Memphis State University basketball games, where the building design created a loud, dynamic environment.

In the Coliseum’s earliest years, the university played an all-white team, but when it integrated its team in the late 1960s with a single African American player and went to the Final Four in 1973 with a largely African American team, the city’s love of basketball was finally and irrevocably color blind. In addition, the building was home to Memphis Wings ice hockey team (it was mainly about waiting for the fights), the American Basketball Association (it was mainly about waiting for Dr. J to visit), and countless wrestling matches (which for some is remarkably what the building is remembered for). An often forgotten footnote is that the first NBA games played in Memphis were the eight “home” games played in the Coliseum by the St. Louis (later Atlanta) Hawks.

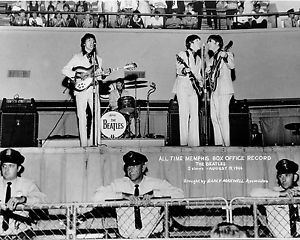

The good news was that the Coliseum opened in time for the British Invasion, with concerts by the Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five (which sang less than 30 minutes), Herman’s Hermits, Peter and Gordon, and Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, but it also opened in time to become the hub for Memphis rock and roll and soul music with concerts featuring a young unknown singer named Otis Redding and Memphis music legends like Rufus and Carla Thomas, Booker T and the MGs, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, the Gentrys, and more.

Good and Bad

Essentially, every big name band, group, or singer found their way to the Coliseum, and the building earned a place in music history when the concert by the Beatles led them to quit touring. We all know the story: coping with the controversy that erupted when John Lennon said the band was more popular than Jesus, the group decided to give up touring when two people threw a cherry bomb onto the stage in the evening concert and the Fab Four thought one of them had been shot. Then again, the incident had followed death threats, a Beatles record burning, city officials threatening to cancel the concert, Ku Klux Klan pickets, a Christian Youth Rally sponsored by 100 ministers at the same time as the concert, and John Lennon himself suggesting that the band not come to Memphis because of its violent tendencies.

For many, the pinnacle of the Coliseum’s history took place in four sold-out concerts by Elvis Presley over two days March 16-17, 1974, and three days later, when he performed one more sold-out concert in order to record an album for RCA.

If the music was the good news, basketball was the bad. In the first six seasons of Memphis State basketball, there was only one winning season. In fact, the dismal Moe Iba years included three years when there were 20 total victories and 56 losses for his “pass the ball around for five or six minutes and take a shot” teams. About the same time, the NBA games became a one-year phenomenon, and the American Basketball Association’s five years with three versions of the Memphis team – Pros, Tams, and Sounds – failed to capture the public’s interest even when Larry Finch and Larry Kenon were drafted.

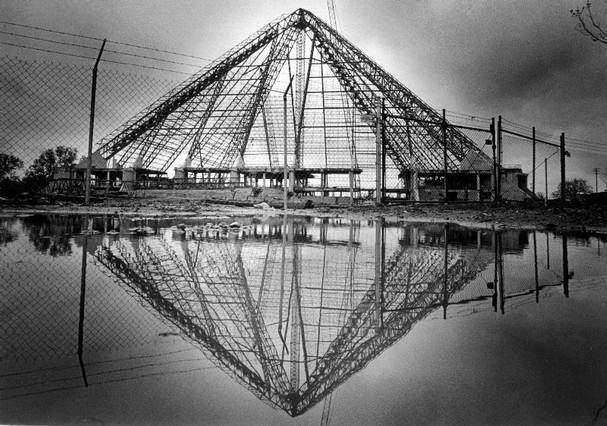

Eventually, the University of Memphis basketball program’s success and promoters’ complaints that they needed a bigger building produced pressure for a larger arena in the mid-1980s. Meanwhile, the idea of a large pyramid being built as an icon for Memphis had been around for decades, and at one point, it had even been suggested for Shelby Farms Park.

Building An Icon To Get A Downtown Arena

The press for a new arena and a city icon collided in the late 1980s, and government officials who wanted the new arena downtown – which produced an outcry for people used to the midtown location – put it into the form of a pyramid to make the argument that it logically should be downtown on the riverfront where it would be seen by the most numbers of people. There had been a brief discussion about “raising the roof” of the Coliseum, but because of the way the building was constructed, it was not practical or cost effective.

Once the downtown location won out politically (it was always a contentious decision with the public which, in a poll years after it opened, were still split 50-50 on the question of whether it should have been built downtown) the question was whether it should be built on the south bluffs or where it is located today. It seemed clear that the south bluffs location would be more prominent, but the Auction and Front Street address was chosen after Memphis developer Henry Turley and Tony Bologna convinced key leaders that the south bluffs were prime for residential development and that handling the parking demand there would be difficult. In support of their position, they made a film of the drive down Riverside Drive that showed that the pyramid would be largely invisible for motorists because it was on the bluffs above them.

As a result, the current Auction and Riverside location was chosen although one county commissioner said it felt to him like a “voodoo site where something bad had happened.” Fortunately, for Memphis, Mr. Turley and Mr. Bologna’s vision of the south bluff’s development has come to fruition, which would not have been possible if The Pyramid had dominated that part of downtown.

It was thought by city and county officials that with the opening of the Pyramid Arena, the Coliseum would close, and in preparation for the day, city and county governments offered the building at no cost to University of Memphis, which declined out of concern about maintenance costs and much-needed capital improvements.

A Battle It Could Not Win

But the closing was not to be. When city and county mayors communicated their opinion to the board members, they refused to comply. Instead, they set out to keep the Coliseum open and use the substantial balances in the building’s bank accounts to do it. However, the Coliseum needed $10-15 million in renovations and upgrades, but city and county governments refused requests for money from an uncooperative board.

The sides hardened even more when the Coliseum Board, in an effort to prevent city and county governments from tearing down the building, filed a successful application in 2000 to place the building on the National Register of Historic Places. The application sealed the fate of the building, because while the city and county governments could not close the Coliseum over the wishes of the board, they could refuse any funding while the board depleted its bank accounts.

The decision by the “runaway board” essentially cost Memphis and Shelby County taxpayers millions of dollars because to be successful, the Coliseum had to become a competitor to the Pyramid, driving down rental rates and revenues at the new arena, creating deficits that had to be made up in city and county funding. Despite public perceptions, The Pyramid was not making big profits from the University of Memphis basketball season. In exchange for its approximately $15 million contribution to the building construction budget, it received a sweetheart deal that meant that its entire year of basketball produced less revenue for The Pyramid than a single sold-out concert.

Despite its board, with the opening of the Pyramid in 1991, the Coliseum began a slow descent into obsolescence. Most marquee acts were playing The Pyramid, and even if they didn’t, it was because the Coliseum had undercut the promoters’ costs there, which meant that the Coliseum was settling for less and sinking into the red with its operating budgets – $400,000 in its last year.

Mass Hypnosis

Truth be told, The Pyramid could not compete with the quality of the Coliseum’s construction materials – and certainly not its acoustics – and in retrospect, it’s unbelievable that our community could be convinced that a “first class, state of the art” arena could be built for $39 million (although the final cost was approximately $62 million).

Nor were the new arena’s comfort and sight lines as good as the Coliseum. While the University of Memphis did not want an arena with 20,000 seats, the building’s seating was expanded by several thousands of seats to satisfy one county commissioner whose vote was crucial for approval of the new arena.

With competition between the two arenas, it was no surprise that both ended up losing money, but what was truly remarkable was that the Coliseum managed to hang on until 2006, when it could not comply with the requirements of the American for Disabilities Act (ADA) and city and county governments were not going to pay for it to be compliant.

When the potential of a National Basketball Association team moving from Vancouver to Memphis surfaced, it became clear just how cheaply the Pyramid had been constructed. The cost to upgrade it to NBA standards was almost exactly the same as building a modern arena, and with the 2002 agreement with the Memphis Grizzlies, that’s what the community set out to do.

Closed For Business

Meanwhile, Memphis and Shelby County Governments made sure that with the agreement with the Memphis Grizzlies, there would not this time be public arenas competing against each other to the detriment of taxpayers. As a result, the governments entered into a non-compete agreement that gave FedExForum priority on all bookings and the team’s best chance to maximize its revenues.

In return, the Grizzlies agreed to city and county demands for it to pay all operating costs of the FedExForum. It was estimated at the time that the deficit for the new arena would amount to at least $5 million a year, but even more, if the non-compete agreement had not been signed, it would have likely meant that taxpayers would pay operating losses at The Pyramid and the Coliseum.

All professional sports experts predicted that Memphis would never get the team to pay the operating losses at the Forum. After all, Nashville taxpayers were paying millions of dollars every year for the operating losses for its National Hockey League arena. It was one of city and county government’s finest hours.

By the time the Coliseum closed for good in 2006, it had languished for several years, and the fact that it managed to stay open longer than the Pyramid is remarkable. (Its closing was part of the City of Memphis’ strict ADA settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice.) After all, at that point, the Coliseum had stayed open 42 years old and The Pyramid had managed to stay open only 13 years before it was obsolete.

Underutilized Public Assets

In 2004, with the move of the Grizzlies from The Pyramid into FedExForum, Memphis Mayor Willie W. Herenton and Shelby County Mayor A C Wharton appointed a special committee to consider jobs-producing uses for the two empty arenas, The Pyramid and the Mid-South Coliseum, and named Robert Lipscomb, director of housing and community development and executive director of Memphis Housing Authority, to serve as primary staff.

After public hearings in the early years following creation of the special committee and a report by Looney, Ricks and Kiss about a family-oriented focus, the Tennessee Tourism Development Zone (TDZ) was identified as a funding source that would allow City of Memphis to access more than $300 million in state sales taxes to redevelop a site that was acres and acres of asphalt. In time, the construction of Tiger Lane and improvements to Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium were approved with the idea that when the TDZ was approved, City of Memphis would be repaid.

Most effective grassroots advocacy campaigns need a villain and unfortunately for Mr. Lipscomb, he was given that role. After the process to find a better use for the Fairgrounds was about nine years old, the debate its future was ignited, and in the process, he was vilified and his motives were questioned in ways that make Donald Trump’s comments seem tame. By that time, he had evaluations and reports that the Coliseum could not be repurposed for a revenue-producing use, much less a use than complied with the non-compete agreement.

Contrary to mythology, he had assembled a team and tasked them for more than a year to consider how to save the Coliseum, what the costs would be, and what the uses could be. In fact, in one of the two dozen presentations about the Fairgrounds development that he made to Memphis City Council, there was a time when a majority of the body urged him to ask them to vote to raze the building. He declined, because he still held out hope that someone would step forward with the money and the concept to use it.

Later, in the face of criticisms about the lack of more recent public meetings about the Fairgrounds, a firm was hired to conduct some and the Urban Land Institute was hired to bring fresh eyes to the Fairgrounds opportunity. In the end, the ULI team could not identify a way to put the Coliseum back into a use consistent with its former uses, recommending the preservation of a part of the building for something akin to a pavilion stage.

Brewing A New Future

We say all this to say we love the Coliseum and some of our fondest memories are connected to that special place, but in the absence of a clear use such as a brewery for Wiseacre Brewery Co., our prediction is that the Coliseum will sit where it is a deteriorating state until it collapses.

It is tempting to hold out hope for other uses – and money – to materialize, we should all draw cautionary tales about the coliseums built in the same era as ours. The Jacksonville Coliseum, opened in November, 1960, and which hosted many of the same concerts and events as the Mid-South Coliseum, was imploded in 2003 to make way for the Jacksonville Memorial Arena.

The coliseum arena in Mobile was opened three months before the Mid-South Coliseum and it held a theater, an expo hall, and an arena. With deficits running as high as $800,000 a year, the Mobile mayor announced that it would close in April for redevelopment; however, the search for a public-private partnership came up empty and the deadline was extended two years to continue the search for a private developer.

We have no animus for the Coliseum, but nostalgia is not a business plan and wishful thinking is not a prescription for profits. Wiseacre is a local and loved local business, and we expect Memphis City Council to give them the opportunity to decide if it wants to engage in one of the city’s most audacious adaptive reuse projects.

#1

The brewery use may not be the perfect solution for everyone, but it could achieve the #1 priority for all Coliseum lovers: preservation of the building – and it might even include some ancillary public uses like the rock-climbing wall, bowling, or a restaurant.

We admire a local company for even considering this location for its brewery, particularly when its emphasis is on a quick decision in order to open on its timetable. The priority for a business is to reduce risk, and there will be some significant risks attached to this building, and we suspect any public dispute produces a risk that could well lead to the choice of another brewery location.

For now, it seems that people who love the Coliseum should also try to love Wiseacre, and if we are to hold out hope, let it be that after Wiseacre executes its immediate business plan, the community can be involved in a discussion about what else the building might house.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

Interesting history of arenas in Memphis.

Our city certainly has wasted a lot of public money over the decades on such projects. The Pyramid has to rank as the all-time low.

In contrast, I saw recently where the Nashville Municipal Auditorium (built

at the same time as Mid-South Coliseum) is still actively used for all kinds of concerts and events and is under the management of Live

Nation. The building is also permanent home to the Musicians Hall

Of Fame. Nashville also opened the Ascend Ampitheatre downtown on riverfront.

Once again, Nashville is just so much smarter than Memphis!

Lol, your schtick is getting old. Too predictable. Try again, ziphead.

And if you look at the Nashville Municipal Auditorium website they have 7 events through the rest of the year on their calendar and I’m not sure they’re blockbusters. So would that schedule be worth $22 million or so in renovations which would likely include city money? The arenas in Southaven and other places aren’t going to go away if the Coliseum is re-opened. And the majority of their acts (country) would still most likely go to MS than midtown Memphis. I’m sorry I just don’t see any way it’s feasible to re-open as an arena. Nostalgia is great but it’s time to move on sometimes.

http://www.nashvilleauditorium.com/events/

Tear it down! We already have enough empty large buildings in Memphis like Sterrick Bldg and 100 North Main.

Geez, how many mistakes are in this mess? I stopped counting at ten.

Then, list them.

We’d be interested in hearing them as well. We were involved in all things related to the Coliseum and Pyramid from 1976 on, so we’d appreciate your input.