So, let’s think this through.

IKEA bought property at the southeast corner of I-40 and Germantown Parkway for $5.6 million four months ago. We assume that the international retailer would not have paid that price unless the company had determined that it was worth it and that the sale price reflected its value.

But now, IKEA is challenging the appraisal by Shelby County Assessor Cheyenne Johnson and wants to ignore the 2015 appraisal of $5.1 million and roll back the appraisal to its 2014 level of $1.25 million. The Shelby County Board of Equalization was willing to go along with this leap of self-interested logic.

But, if IKEA truly believed that the value was worth $1.25 million, wouldn’t it have refused to pay four times that amount? Isn’t it logical that if the market says the property is valued at $5.6 million because that’s what a buyer was willing to pay for it, the assessor should appraise it in that range?

The assessor’s office’s most recent appraisal for the IKEA site was $5.1 million, which seems highly reasonable and in line with the recent sale price.

Doing Her Duty

While IKEA is a highly-coveted and trendy retailer, the barbs and attacks on Ms. Johnson for seeking a fair appraisal on the proposed site of its Memphis store are misplaced, since she is only doing her job. And that job is to appraise property accurately, fairly, and equitably – without fear or favor.

Her appeal of the $1.25 million appraisal by the county board of equalization is well within her authority and for us, it reflects her sincere commitment to her responsibilities and in keeping with her oath of office to serve the public.

Already, IKEA has had the rules for PILOTs changed so that it could be the first retailer to receive a tax holiday – IKEA’s holiday is worth $10 million over 11 years. Shortly after receiving its tax freeze, it demanded better bus routes to the store site which seemed especially ironic since it had just refused to pay taxes for public services like MATA.

As for the current tax controversy, it means that IKEA is threatening to not build a store in Memphis as the result of an argument about paying approximately $300,000 more in property taxes, which is about what the retail giant makes in revenues every two and a half minutes. In any language, it makes no sense.

Tale of the Tape

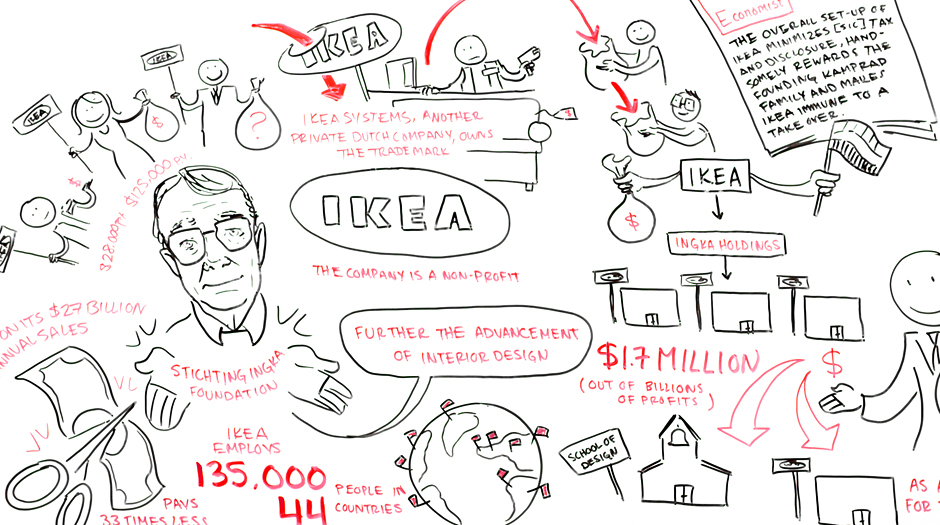

IKEA annual revenues: $29 billion

Number of stores: 301 (plus 30 franchised units)

Number of employees: 135,000 in 44 countries

Structure: Nonprofit

Yearly taxes waived by city-county PILOT: $864,000

Approximate yearly amount of taxes for schools waived: $150,000

Yearly tax amount at dispute with Shelby County Assessor: $300,000

IKEA’s hourly revenues: $3,310,502

IKEA’s Nonprofit Mission:

To “offer a wide range of home furnishing items of good design and function, excellent quality and durability, at prices so low that the majority of people can afford to buy them.”

Excerpts from the Economist, May, 2006:

FEW tasks are more exasperating than trying to assemble flat-pack furniture from IKEA. But even that is simple compared with piecing together the accounts of the world’s largest home-furnishing retailer. Much has been written about IKEA’s remarkably effective retail formula. The Economist has investigated the group’s no less astonishing finances.

What emerges is an outfit that ingeniously exploits the quirks of different jurisdictions to create a charity, dedicated to a somewhat banal cause, that is not only the world’s richest foundation, but is at the moment also one of its least generous. The overall set-up of IKEA minimizes tax and disclosure, handsomely rewards the founding Kamprad family and makes IKEA immune to a takeover. And if that seems too good to be true, it is: these arrangements are extremely hard to undo. The benefits from all this ingenuity come at the price of a huge constraint on the successors to Ingvar Kamprad, the store’s founder (pictured above), to do with IKEA as they see fit.

Although IKEA is one of Sweden’s best-known exports, it has not in a strict legal sense been Swedish since the early 1980s. The store has made its name by supplying Scandinavian designs at Asian prices. Unusually among retailers, it has managed its international expansion without stumbling. Indeed, its brand—which stands for clean, green and attractive design and value for money—is as potent today as it has been at any time in more than 50 years in business.

In this section

The parent for all IKEA companies—the operator of 207 of the 235 worldwide IKEA stores—is Ingka Holding, a private Dutch-registered company. Ingka Holding, in turn, belongs entirely to Stichting Ingka Foundation. This is a Dutch-registered, tax-exempt, non-profit-making legal entity, which was given the shares of Mr Kamprad in 1982. Stichtingen, or foundations, are the most common form of not-for-profit organisation in the Netherlands; tens of thousands of them are registered…

…If Stichting Ingka Foundation has net worth of at least $36 billion it would be the world’s wealthiest charity. Its value easily exceeds the $26.9 billion shown in the latest published accounts of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is commonly awarded that accolade.

Measured by good works, however, the Gates Foundation wins hands down. It devotes most of its resources to curing the diseases of the world’s poor. By contrast the Kamprad billions are dedicated to “innovation in the field of architectural and interior design”. The articles of association of Stichting Ingka Foundation, a public record in the Netherlands, state that this object cannot be amended. Even a Dutch court can make only minor changes to the stichting’s aims.

If Stichting Ingka Foundation has net worth of at least $36 billion it would be the world’s wealthiest charity. Its value easily exceeds the $26.9 billion shown in the latest published accounts of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which is commonly awarded that accolade.

The Kamprad foundations compare poorly with the Gates Foundation in other ways, too. The American charity operates transparently, publishing, for instance, details of every grant it makes. But Dutch foundations are very loosely regulated and are subject to little or no third-party oversight. They are not, for instance, legally obliged to publish their accounts.

Under its articles, Stichting Ingka Foundation channels its funds to Stichting IKEA Foundation, another Dutch-registered foundation with identical aims, and which actually doles out money for worthy interior-design ideas. But the second foundation does not publish any information either. So just how—or whether—Stichting Ingka Foundation has spent the €1.6 billion that it collected in dividends from Ingka Holding in 1998-2003 remains hidden from view.

IKEA says only that this money is used for charitable purposes and “for investing long-term in order to build a reserve for securing the IKEA group, in case of any future capital requirements.” IKEA adds that in the past two years donations have been concentrated on the Lund Institute of Technology in Sweden. The Lund Institute says it has recently received SKr12.5m ($1.7m) a year from Stichting Ikea (which also gave the institute a lump sum of SKr55m in the late 1990s). That is barely a rounding error in the foundation’s assets. Clearly, the world of interior design is being tragically deprived, as the foundation devotes itself to building its own reserves in case IKEA needs capital.

Although Mr Kamprad has given up ownership of IKEA, the stichting means that his control over the group is absolutely secure. A five-person executive committee, chaired by Mr Kamprad, runs the foundation. This committee appoints the boards of Ingka Holding, approves any changes to the company’s statutes, and has pre-emption rights on new share issues.

Mr Kamprad’s wife and a Swiss lawyer have also been members of this committee, which takes most of its decisions by simple majority, since the foundation was set up. When one member of the committee quits or dies, the remaining four appoint his replacement. In other words, Mr. Kamprad is able to exercise control of Ingka Holding as if he were still its owner. In theory, nothing can happen at IKEA without the committee’s agreement.

That control is so tight that not even Mr Kamprad’s heirs can loosen it after his death. The foundation’s objects require it to “obtain and manage” shares in the Ingka Holding group. Other clauses of its articles require the foundation to manage its shareholding in a way to ensure “the continuity and growth” of the IKEA group. The shares can be sold only to another foundation with the same objects and executive committee, and the foundation can be dissolved only through insolvency.

Yet, though control over IKEA is locked up, the money is not. Mr Kamprad left a trapdoor for getting funds out of the business, even if its ownership and control cannot change. The IKEA trademark and concept is owned by Inter IKEA Systems, another private Dutch company, but not part of the Ingka Holding group. Its parent company is Inter IKEA Holding, registered in Luxembourg. This, in turn, belongs to an identically named company in the Netherlands Antilles, run by a trust company in Curaçao. Although the beneficial owners remain hidden from view—IKEA refuses to identify them—they are almost certain to be members of the Kamprad family.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

You very nearly had me nodding in agreement with you, but the majority of your article (about how IKEA is governed internally) nearly had me nodding off and had nothing to do with your thesis that IKEA should pay the higher taxes and shut up about it.

Your article also shows a misunderstanding of property assessment for taxation. According to the assessor’s website, the purchase price for a property isn’t factored at all into the appraisal. Property use, characteristics, market conditions, and sales of similar properties are used in the appraisal. But, the purchase price of that land is not one of those factors. This is done intentionally so that someone making a poor deal (paying too much or too little for a property) doesn’t throw off the tax system. You advocate IKEA paying more taxes for a higher purchase price. But, would you advocate that they pay less tax for a lower purchase price? If IKEA had bought the property for $1, would you advocate they pay property tax only a $1 appraisal? I’m guessing your answer would be ‘no.’

There’s a process for these things and it’s good to see that process being used. Your article, though, sounds like its all about higher tax assessments, even if that means that IKEA pulls out. At some point, I think we need to consider what the impact is for local consumers (can’t buy things if stores can’t locate here) and what the value might be of aggressive taxation (tax collection even on a lower value property nets more than no collection at all). Two previous articles focused on bringing millenials to Memphis. Millenials like to have hip and in-demand commerce close by. IKEA has a huge millenial following. If we’re willing to to say “my way or the highway” to these millenial attractants, we’ll push away the millenials you are hoping to attract, too.

George, I’m in total agreement with you. IKEA may be a “trendy” retailer, but that equals HUGE revenue in the form of sales taxes. People drive miles and miles to shop at IKEA. I lived in St. Louis for 10 years and knew people who would drive to the Chicago IKEA because that was the closest one for many years. Will this city honestly be better off with that land sitting unused, 150+ less jobs, and essentially no tax revenue generated from that land?

Sale price of subject parcels is most definitely taken into consideration. A determination must be made if the transaction was an arms length transaction, or one that was influenced by some type of distress sale. As long as the sale can be determined to be an arms length sale/was exposed to the market, it would provide significant weight in determining the value of the parcel.

I agree, the logic of paying $5.6 million for a piece of land and then arguing that it is worth just $1.25 million for tax purposes makes no sense at all. It seems like IKEA is just trying to bully Memphis into the privilege of having a store. Isn’t good business building where you think you have a good market and not building where you don’t? If IKEA decides to bolt and not build here, we can only hope that they get proven right and are able to sell their land here for $1.25 million. It would be a pleasure watching them swallow that $4.35 million loss.

George, the appraisal was done BEFORE the sale (only sales dated before Jan 1, 2015 can be used for a 2015 assessment), therefore it would be impossible for the assessor to have used the sale. The point is IKEA clearly agreed that this value is pretty close to correct considering they paid $500,000 more than the $5.1 million appraisal.

Funny, but when we purchased our house, that price immediately became the appraised value.

George: Glad we could help with your sleep. We received emails asking us to explain the nonprofit structure we mentioned yesterday on Facebook. That said, the structure is relevant to us because it speaks to a company culture that suggests that it believes it shouldn’t ever pay taxes and it’s up to the rest of us to pay for the public services it receives.

Look at the County Assessor’s website under the ‘Appraisal’ heading: (https://www.assessor.shelby.tn.us/Content.aspx?key=ProcessAppraisal). Nowhere does it mention that the sale price is factored into the appraisal.

You can also look at appraisal and sales data for just about any property in the County. I have yet to find one where the total appraisal and latest sales data match. Sometimes the appraisal is higher than the sales data, sometimes it’s lower. We all know that property sales are negotiations and may be influenced by things that don’t have much to do with home value. When we bought our current home 2 yrs ago, a few repairs were needed and the sellers were offering to include 1 yr’s worth of a home warranty (valued at $500), but not make the repairs (stuck window, fireplace work, etc) that were valued at $1000. We decided that the repairs meant more to us than the warranty, so we countered that we would go up on the price by $500 if they dumped the warranty and made the repairs. That impacts the sale price, but not the appraisal. The property is the same with or without that $500 difference.

There are numerous statements on the Assessor’s website saying that appraisals are not sales figures and are not guidelines for sales figures. The sale figure is mostly irrelevant. The important part is what other similar parcels are selling for, according to the Assessor’s website.

This isn’t surprising at all given how desperate Memphis is for any type of new economic development.

IKEA has obviously seen just how freely and poorly Memphis administers PILOTS and other tax incentives so you can’t really blame them for trying to squeeze out every last nickle.

If they opt not to build here I think it’s no big deal. IKEA is just another big box retailer selling cheap Scandanavian furniture and the 150 jobs don’t pay a lot either.

Clint:

Are 0 jobs better than 150 jobs? I don’t think those potential employees currently earning $0/hr would agree.

Fascinating article on all counts.

There is a difference between appraised value and assessed value of properties. This article deals with residential mostly, but definitions apply to commercial as well:

http://www.zillow.com/wikipages/Assessed-Values-vs-Appraised-Values

Thanks for the information.

Memphis certainly doesn’t fit the “Smart City” description in this instance. What other city would put this project at risk over this relatively small amount of money in the grand scheme of things? This is one of the most impoverished cities in the nation. To say that that 150 jobs and tax revune is “no big deal” is asinine. Memphis always gets what it deserves.

I think Evil is correct. The assessor appraised the property at $5.1 million and the Board of Equalization reduced it to $1.25 million before Ikea’s purchase. Cheyenne Johnson is appealing the BoE reduction just like any of us can appeal a decision to the State if we don’t agree with the BoE decision.

I understand that the assessor can’t change an appraisal until the next county-wide reappraisal. Even if I bought my house for four times its current appraisal, the next reappraisal would reflect a composite of similar sales in my neighborhood or if no data in my area, then comparables in similar situations elsewhere. I think George made this point.

Smart City’s house appraisal probably came in a county-wide reappraisal year when other surrounding houses were selling for similar prices.

An interesting factoid: you can’t use comparable appraisals in your neighborhood to argue for a lower appraisal, only comparable sales.

There becomes a point when we are simply the punch line to the old joke: “Now we know what you are, we’re just haggling over the price.” Giving these massive incentives for retail jobs is anything but smart.

Are we ever willing to draw a line in the sand and not go over it? Isn’t $10 million in waived taxes enough? Is there any line that we will not cross?

When it comes to economic development, we behave like someone in an abusive relationship, and you know how you generally end up in these kinds of relationships – abused.

Flip the equation, if you think the amount of taxes is no big deal, and IKEA is a $30 billion company that could pay them out of petty cash, it seems to us that they are the antagonist in this story, not the assessor. But if IKEA is willing to say that it will give priority for these jobs to people in poverty, we’ll reconsider, but you and I both know that isn’t going to happen so being an impoverished city is a fact but not a determinant.

George: All we’re saying is that we know many people who bought a house for more than the county appraisal and the amount was changed to the sale amount.

My beef is this deal was sold under specific parameters and values and what assessor has done is interjected her office into the middle after those agreements were negotiated. This is a huge positive project for the city and that land has and most likely will stay vacant if they pull out. The economic benefits massively outstrip what the extra tax revenue may be if the assessor prevails. Classic stepping over dollars to pick up pennies. What is her motivation here? They say they aren’t allowed to consider other factors but that is a ludicrous notion. The appeal is either political or pride, both are misguided.

David:

We wonder if when the economic development types were wooing IKEA, any one bothered to ask the assessor for her input. Sometimes people get so busy selling and trying to close a deal that they make assumptions without validating them.

More to the point, no one can make an agreement on her behalf – she is a constitutional officer and has an obligation to perform her duties. It’s also worth remembering that these are retail jobs and in other cities, clerks are being paid around $25,000. We seem to be creating a lot of retail jobs right now, so we aren’t as worried about needing to replace them if IKEA walks away.

Sara and George:

I have mixed feelings about the Ikea deal. On one hand, the 150 jobs are probably low wage and Memphis doesn’t need to be signaling that we will give tax breaks for low wage jobs. Also, Ikea can do without a tax break and still make a lot of profit. They just don’t need the tax break.

On the other hand, if there is significant out of town customers from Little Rock, Jonesboro, Jackson, TN, Jackson, MS, Oxford, Tupelo, etc. then these jobs will be supported by “new money” coming into our economy and other expenditures by these visitors will add more. Thus, Ikea is like an “export” business for Memphis that drives the creation of other jobs, unlike most retail that merely shifts money from one part of Memphis to another part. The only problem is that the profits of Ikea don’t stay in Memphis and we can’t own any stock in the company.

For George- It may not state it. However, a sale of a subject property is the most desirable comparable, assuming it is an arms length transaction. Now, if it occurred after the effective date that the Assessor’s Office is using, let’s assume Jan. 1, 2015, and there is no evidence/none presented to support that it was under contract before that date, then the sale should not be considered as evidence to raise or lower. That’s not to say that the parties before the Board of Equalization are not going to bring it up. Both parties, the Assessor and the tax rep, have an obligation to represent the interests of their clients: Shelby County for the Assessor and the taxpayer for the tax rep. In addition, if the property was listed for sale, that information could be presented to the board as well. When it comes to residential and commercial, the Assessor does not have access to the local MLS (as of 2011- not sure if that has changed). However, residential listings can be found on Trulia, Yahoo, etc. Commercial listings can be found on LoopNet. Whether or not the Assessor presents that as evidence, is up to the Assessor. And, whether the tax rep objects to that information is up to the tax rep. The Board then makes their determination of value based on the evidence presented. I would have liked to have been at the board meeting to hear this one discussed, as I would imagine it was a very heated discussion.

No worries Memphians. You guys can just drive to Williamson County to our Nashville IKEA. That way you won’t have to be worried about getting cheated out of your property taxes by the evil IKEA big business empire. Maybe that piece of land can be turned into a nice City Gear or Dollar Store. Maybe a Family Dollar superstore? That will bring in the business. We will see you Memphians in the rearview.

http://www.commercialappeal.com/columnists/ted-evanoff/evanoff-catching-up-to-nashville-2096ce8a-43fc-5837-e053-0100007fc755-329586771.html

Memphis really is its own worst enemy. So backward in every way.

Let’s put things into perspective. I have several pieces of IKEA furniture which are shoddily made and do poorly in moves. If folks are worried that an IKEA is requisite to attract millenials, I would suggest that people interested in a dynamic city will not likely be impressed by a big box store adjacent to a highway in a sprawling part of the city. Main point: the city shouldn’t prostitute itself for a big box store.

Chatul:

Thanks for the comment. We thought we had millennials nailed down when we opened the Cheesecake Factory. 🙂

It seems like we’re always trying to be one of the cool kids when Memphis was cool before cool was cool.

This is one backwards town! The same people saying who cares about IKEA coming to town were the same people arguing against the NBA coming to town. Memphis was probably trying to “be cool” by having an NBA team?? What a joke Memphis city is with its stagnant population growth, lack of jobs, rampant crime, and inept government officials running the show. It’s a total clown show down there. Why would any major company want to call Memphis home?

Thomas: Actually, I negotiated the contract that brought the Grizzlies to town, but try to reach opinions based on the individual merits of each case.

Smart City Memphis: I’m Batman

Very mature. Just check the public record or ask anyone on the original ownership group. I’m very proud to have done it along with Rick Masson.

Cheyenne must not have been put on the IKEA payroll…

Every city wants an IKEA!! What the hell is wrong with you people down there? Haha I’m sure they’ll just go to Nashville. That’s a nicer city anyway. You guys need a new assessor.

“Every city wants an IKEA!! What the hell is wrong with you people down there?”

I would suggest many of us haven’t been overtaken by the spirit of materialism and covetousness. I do like their Köttbullar meatballs though.

Every county should have an assessor who takes her job as seriously and honestly as Cheyenne Johnson. Her position in this controversy is yet more proof of that fact.

Thanks, Chatul, for putting it in perspective. We understand that some people disagree with the assessor’s point of view and that’s fine. What we don’t understand are the people who use any excuse to trash Memphis.

Agree with Chatul (aside from the meatballs) and proud of Cheyenne for doing her job – hoping there’s a resolution that makes since for Memphis. Will be interesting to see if Strickland has any impact on the PILOT mentality of “let’s just give away the store because we’re so lucky some big name company wants to come and make very little economic impact and give us 100 low wage jobs.”

Smart City, we appreciate your big picture/long view and wish those in control of these issues read this blog. We also wish that you could block the Nashville cheerleader who now posts on every single thread under 10 different names seemingly just for the kicks of insulting Memphis at every turn. Somebody has too much time on their hands and needs to go get one of those fancy new IKEA jobs…

I agree with the property assessor. However, it seems that your post leaves out a major point of contention – the re-appraisal of the property between county-wide re-appraisal years. From what I have read the splitting of the property warranted the re-appraisal, but many people are asking why it was re-appraised outside of the regular time frame.

Your argument would be better made if you addressed this point of contention.

Somehow I feel Memphis “leaders” will do what they do best and make themselves even more of a laughing stock on a national level when this is all said and done.

Or, we may improve our national image by refusing to be taken advantage of by every greedy company that comes to town.

The comments on this thread in particular show how very much a “small town” Memphis really is. One would think a chain furniture store like IKEA is the only business game in town.

Memphis is certainly a troubled city in the middle of major decline in all kinds of ways.

The Memphis region undoubtedly has serious structural problems that have existed for many decades, but for those who only want to see the negatives, you might want to scroll through this recent presentation by Andy Cates (thanks to Daily News for posting it online):

http://www.memphisdailynews.com/Editorial_Images/24010.pdf

Tom. Agree that the list of projects in the presentation are good but they are really small potatoes when compared to what is happening in other cities. Memphis has so many systemic problems — led by high poverty and crime. Business and job growth here is anemic and we are seeing a decline in population. All those things do not bode well for the future of Memphis. We can all be cheerleaders for our city, but we are far behind and losing the game by a huge margin.

It seems that these investments do compare to many of our peer cities, but we’d love to see comparables if you have any. According to New York Times, there is more than $2 billion in new construction under way in Nashville, so we seem to be much more competitive to that amount than previously thought (understanding that different cities calculate capital investments differently so this isn’t scientific).

Memphis does have structural problems that we’ve written about for a decade. The question now is whether these projects can stimulate in-migration, talent retention, and momentum that can improve these century old problems.

As we wrote recently, being part of a region that has its own share of problems – unlike Nashville, Atlanta, Louisville, Indianapolis, etc. – is a drag on Memphis that is an anomaly when compared to others.

Maybe things are turning around, but we these projects need to include plans for the neighborhoods that surround them if they are to be fully transformative.

Yes! I’m sure taking a stand against the evil IKEA juggernaut will improve Memphis’s national image. After all, getting taken advantage of by corporate America is what’s really hurting the city’s image!

Come on. Let’s be real!

It’s bizarre that everybody in Memphis is so obsessed and so envious about Nashville. There is just no comparison. Nashville is a boom town and left Memphis in the dust years ago. Comparing the two cities is like night and day.

Spending time comparing Memphis and Nashville is a mere distraction from getting done what needs to be done here. As we have said before, NO city in he Southeast U.S. compares with Nashville right now. Memphis has its own assets and authenticity to leverage into a highly successful city.

Clearly, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital believes in the future of Memphis and that vote of confidence is convincing and compelling.

Actually it appears that few if any residents of Memphis posting on this site are obsessed with or envious of Nashville. Instead it appears that at least one individual is obsessed with Nashville and spends much time posting under various names in their desperate attempt to portray said municipality as some booming metropolis. I am all for open and honest dialogue, because a true dialogue requires those two factors. This one individual is being neither open nor honest in their posting under various names and constant insinuations that distract from the topic being discussed. If Smart City Memphis wants to continue to support a true dialogue, regarding various issues, it is past time to block this individual from posting.

After all, this poor ignorant soul is welcome to share their insight on their own blog.

Congratulations everyone.

It is the “IKEA WAY”.

Just , count the number of Jobs created on the opening day.

Looking forward to the opening day

I think the admin of this site is actually working hard in support of his web page, since here every material is quality based information.