I met Frank McRae 49 years ago.

He was 34 years old and I was in high school. I introduced him to Bob Dylan and he introduced me to the social gospel, and it was a convergence that transfigured my whole life.

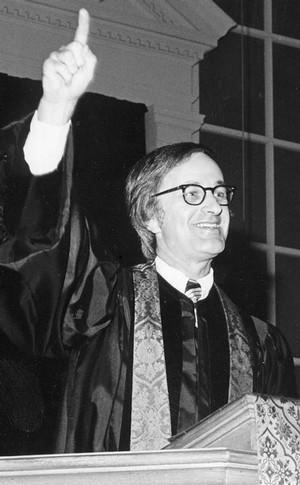

Frank was minister of the Methodist Church on the town square in Collierville, where residents were still bragging that the town’s population had broken 2,000 in the 1960 Census. It was several years before he was to become a towering figure in the white church in Memphis during the days of the sanitation strike and the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

My wife, Carolyn, and I bumped into Frank and his wife, Becky, in late February in the MRI waiting room at West Clinic. It was obvious that he was gravely ill, and he said his situation wasn’t good and that he was preparing to wrap up his life. Becky later emailed that he was too weak to have visitors.

Despite the forewarning, it was still a kick in the gut to read in The Commercial Appeal over the weekend that he was in hospice care. Today’s newspaper carried news of his death at the age of 83.

It is simply incomprehensible to imagine a world without him.

Finding the Meaning of the Faith

When we met so many decades ago, he was honing the message of his ministry in a small, conservative, all-white church in Collierville. Already, he was pushing the congregation’s comfort level, calling on them to consider that living the meaning of their faith required them to consider the poor, the voiceless, and the powerless.

It was a message that upset more than a few members, but fortunately, one of Rev. McRae’s closest friends was the Collierville vice-mayor (later to become the mayor), Herman Wright Cox Jr., whose opinions may have diverged in many respects from his minister but whose defenses of him were timely and persuasive.

Despite the level of discomfort that resulted from his message, there was no mistaking to everyone that Frank was destined for important things.

My mother worked for Mr. Cox, and through him, I was introduced to Frank McRae. My family attended the Collierville Baptist Church where I had questioned some core religious teachings, particularly as it related to defending a status quo that included segregation. I think originally Frank was recruited to save me from myself, but instead, as only he could do, he validated me, he legitimized my journey, and he became a cherished friend.

Music To My Ears

When I questioned the inerrancy of the Bible in my Baptist Church, I was summoned by the minister who answered my question, why should I believe this?, with “Because I tell you to.” When I asked the same question of Frank, he told me to bring my own understanding to the Scripture and suggested that blind dogma could obscure faith more than illuminate it. For a teenager struggling to make sense of things, he was a lifeline. He told me how Christianity plays out its relevance in the social gospel, and I told him about the relevance of Bob Dylan’s protest songs.

So we started listening to records in my second floor bedroom in my house just off the Collierville town square and a three-minute walk to his church. When I bought “The Times They Are A-Changin’” album, I called him excitedly at his office so we could find a time get together because I wanted him to hear “With God On Our Side.”

He told me to come to the church right away and we’d listen to it. I assumed that he had a record player in his office, but instead, it was connected to the speakers in the sanctuary, where we took our places in a middle pew and listened to the song. We talked about the ways in which people use the Bible to bludgeon and marginalize other people and how people are called on to act on their faith, most of all when it’s unpopular.

Destined for Downtown

He talked about the relevance of John Wesley’s words in the segregated South: “Do all the good you can by all the means you can in all the ways you can in all the places you can at all the times you can as long as ever you can.” As he pointed out, it didn’t say to do all the good you can with people who look like you or people with means or people who believe what you believe.

These were radical ideas in the early 1960s, but particularly in a town in denial about the changes that were already under way.

He may have been in a small town but his heart was always in the city. One day, he played me the song, “Downtown” by Petula Clark. It had really spoken to him, because he said that it is downtown where Christianity would prove if it is merely words or if those words could become the actions inspired by a social gospel. He especially like the lyric: “And you may find somebody kind to help and understand you, someone who is just like you and needs a gentle hand to guide them along.”

It may have been pop music to most of us, but to Frank, it was a harbinger of where his ministry would take him. He even later preached a sermon to his Collierville congregation about the importance of downtown in the Bible and to the future of Methodism.

Passing the Test of Faith

Frank left Collierville for Memphis in 1967 where he became the youngest district superintendent for the Methodist Church. Prior to his move, he told me to remember one of his favorite Bible verses: “If a man say, I love God, and hateth his brother, he is a liar: for he that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen.”

Once in Memphis, he answered the question we had discussed so often: are we as Christians prepared to act on our faith when it is put to the test? There was no surprise for me in how he answered – in the only way he knew how. He took his place on the front lines of the civil rights movement urging for resolution of the sanitation strike.

As superintendent, he served on the social action committee of the Memphis Ministers’ Association. He was also a friend of Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb, and he pleaded with him to negotiate with the sanitation workers’ union and defuse the volatile environment, but in the end, Dr. King was to die before political reason prevailed.

While the civil rights movement was a political movement, Frank always understood that it was just as much a spiritual movement. It was not just that equality was a political concept but it was fundamental to who we are as people of faith. It was a point of view that he articulated with Rabbi James Wax of Temple Israel and Father Nicholas Vieron of Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church as they led the handful of white ministers who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with African-American clergy.

Words Into Action

The sanitation strike was a seminal moment in the history of Memphis, but it was also a seminal moment in the history of the U.S. Frank understood this, and because of it, he accepted the friendships he lost and withstood the threats he received because this was the test of his faith that he had so well-prepared himself for.

In hindsight, it seems logical that the arc of Frank’s entire life would lead him to St. John’s United Methodist Church. There, he was a co-founder of MIFA, Friends for Life, and church outreach programs to the homeless, to those with AIDS, the disenfranchised, and those in need. Along the way, he also breathed life into Scott Morris’s concept for a health ministry and named him an associate pastor at St. John’s.

Frank’s most famous sermon was “The Queen is Dead.” It called on St. John’s, whose history was as a grand Memphis church but whose influence had waned as its congregation moved east, to become a servant church. “We will have to learn how to be servants and not masters,” he said. “We will have to give up much of our financial security. We will have to reorder our schedules to spend more time with the needy. We will have to spend more time with strangers than with friends.”

I did not hear that sermon. It was several years later that my family followed him to St. John’s. The sermon that I remember best was “Who are the saints?” It was classic Frank McRae. It was thoughtful, logical, smart, and full of grace.

Who Are The Saints?

He said that sainthood for him wasn’t about the giants of the faith and the powerful of the church who set policies, make the rules, and decide on doctrine. Rather, the saints are the people moving among us every day who care for the poor, fight for the less fortunate, and open up their hearts to those the rest of society vilifies. They don’t do it for praise or for money, but because they are living out the meaning of their faith.

Frank and I tried to have a yearly lunch together to hash over old times and talk about the issues that matter to Memphis and its church. Between visits, I often listed to a cassette tape of that sermon.

He asked the question: Who are the saints?

His life answered it: You are, Frank.

Beautifully written. Frank was always gracious to me ever since I came to Memphis 14 years ago. I was impressed with his life-long passion for justice, but also the compassion he had even for his friend Mayor Loeb. He tried to stay connected with him, even though he disagreed strongly with his policies. In addition to being a social prophet, he was also a darned good pastor. He certainly was to this Presbyterian pastor!

There is a huge void in Memphis, but we are a better people because of Frank.

Sometimes someone touches your life for a moment and remains in your heart forever. For me, that someone is Frank McRae. What a wonderful man who lived as he preached. Thank you, Tom, for bringing Frank into my life.

Well said. Thank you.

Had no idea of his passing. Shedding tears for this wonderful man today. He was a kind and inspiring man and I will always remember my time with him at St. John’s. We had so much fun with him at vacation bible school – one summer he sent us across the street to the new Church Health Center and had us opening up prescription samples and repackaging them so that the patients would receive more doses than came in the pharm samples. He taught us so much as we worked alongside him at the soup kitchen. He didn’t flinch or laugh when my 8 year old self hugged him and said “goodbye St. John,” assuming his name was the same as the church’s. I have so many fond memories of this man who was larger than life. He did so much for this city and he will always be remembered.

A fascinating Memphian. Thanks for the great story.

What a well-written and courageous tribute to a wonderful, loving servant of the Gospel. I am moved by the quality of your words, the quality of the man and the huge amount of work left to do ending fear and hatred in our city, nation and around the globe.

May we all find strength to do our parts.

Thank you, Tom, for this lovely tribute that captures Frank so well. I am fortunate to have had his presence and influence in my life since my high school days as well when he was my district superintendent and a friend of my father. His personal and spiritual counsel was invaluable to me in my young adult years, especially in the days after my father’s death when I lived away from Memphis and faced new challenges. I still have Frank’s letters, which were always so encouraging and gave me the confidence I needed to make my own decisions. I was honored to join St. John’s when I returned to Memphis and was so pleased that he officiated at my wedding and the baptisms of my children. I am a better person because of Frank, and certainly, the city of Memphis is a better place because of his courage, leadership and compassion. May we all live our lives as he did, in service to God and our fellow beings.

Thank you for this beautiful tribute to Frank McRae. It brought back fond memories of the minister I knew while attending St John’s in the 1980’s, early 90’s. For our family he did weddings, many funerals, and christened my son. No matter the occasion he always had the words to inspire or comfort. He had a great since of humor. My heart is heavy for his passing…