City Hall has been off the grid for 25 years and our city has paid the price.

It appears things are finally turning around.

It’s been a long time since Memphis has been in national discussions about policy, government reform and public innovation. It’s been a rare thing back to the 1970s for a Memphis mayor to attend a national think tank conference or to be a regular at the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

The importance of these kinds of events is often lost on the public, but it is in being part of the network of people discussing, debating and solving tough urban problems that cities get attention of the foundations and the organizations that control experts, research and money. Memphis fell out of this network and off the grid of cities whose leaders were visible and active in these national conversations.

Because of it, Memphis’s national image was susceptible to a national beating whenever our dysfunction and division grabbed another national headline. There was so rarely anyone in the know who could tell a different story about Memphis or point to something under way that contradicts perception.

Serendipity Works Too

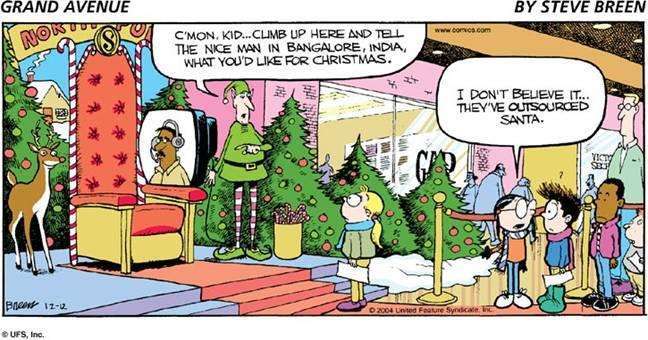

An article in yesterday’s Commercial Appeal by City Hall reporter Amos Maki was an indication of how much things are changing. In the article, Memphis Mayor A C Wharton acknowledged that he was thinking about setting up a competitive system for sanitation services. It could involve outsourcing to a private company or it could involve current sanitation workers setting up an enterprise to bid on the work themselves.

City government’s interest in injecting competition into the delivery of public services is way overdue, and there’s no substitute for a little serendipity. It was the combination of a little serendipity and the new City Hall interest in engaging in policy discussions that spawned the new look at garbage pick-up.

Already, Mayor Wharton has gotten involved in important policy discussions and program development with the Brookings Institution, National Endowment for the Arts, CEOs for Cities and the White House Office of Urban Affairs. Last year, before Mayor Wharton was even elected, Stephen Goldsmith, one of the smartest people in America on government and government innovation, was invited by Leadership Memphis to be the annual speaker in its March community luncheon.

Rebuild Government was equally impressed with him, and he’s writing articles for it to inform voters about the issues that matter as a new charter is being written by the Metro Charter Commission. The first one, on law enforcement, was emailed out Friday. That said, anyone who cares about public policy or government reform has been reading Mr. Goldsmith’s widely-quoted books or columns for years.

Competition Matters

At Leadership Memphis, Mr. Goldsmith – Harvard University professor, author and former Indianapolis mayor (1992 – 2000) – made a compelling case for injecting competition into city governments and for better engaging neighborhoods to set agendas for themselves.

Key points by Mr. Goldsmith:

– The government is delivering fewer services, with the private sector delivering more public services. Since President Clinton’s second term, the number of government employees has fallen as the number of contractors and vendors has risen. This trend will accelerate with the retirement of 40% of all public employees within the next six years. Expect more outsourcing to business of infrastructure, social services, and other traditional government activities.

– Projects should be framed to maximize public value. It is productive to view a project in terms of the end value it will bring the public. The question for government officials to ask is, “What is the value we are trying to create?” Such framing yields an answer of “public health,” not “public hospital”—opening the door to innovative types of public/private partnerships.

– Privatization of government services tends to be considered bad by the left and good by the right. But that is a false dichotomy. Both private and public sector approaches have positives and negatives. The issue is how they can work together to deliver the best of both worlds to create optimal public value.

Big Payoff

– There is constant tension between accountability and flexibility. Government has a responsibility to be accountable, and a high-accountability ethos is baked into its process; business needs to be creative and flexible to be able to envision and execute better solutions. The government’s challenge in a public/private partnership is to manage the outcomes but not the process. The business partner’s challenge is to ensure it preserves the ability to exercise discretion. It is critical that both sides agree on the outcome.

– The clearer the rules and lines of authority, the more likely that a public/private partnership will deliver the intended public value. Conversely, the value is less certain when the government has fuzzy rules, without specifying performance and quality standards.

Mr. Goldsmith was elected on a platform of privatization and unsurprisingly city employees, especially union members, were not pleased. But something surprising did happen. When he met with the first target for privatization, the costly city garage, its employees pushed back and discussions produced a new idea: the union employees of the garage would respond to the bid request for garage operations. When it was submitted, it proved that there are no experts on cost savings like employees themselves, and the garage employees proposed that they would not get a pay raise but a percentage of the savings.

And savings there were. More than $400 million in costs were cut over eight years, producing solid proof of Mr. Goldsmith’s theme that competition actually “liberates” employees from a bad business system.

Power to the People

Meanwhile, at the neighborhood level, he divided the city by areas and set up teams to serve them rather than structuring city government by function. As a result, each neighborhood had a team assigned to it that knew its problems and needs, but more to the point, a team that responded to a plan developed by the neighborhood itself. One thing that he mentioned that caught our attention was that he entered into 500 contracts with churches and neighborhood groups for management of their neighborhood parks.

What’s always been interesting to us that the new enlightened leadership and neighborhood-centered policies did not stem from a crisis. Indianapolis had a low tax rate, good business growth and strong financial indicators (credited by its mayors to its consolidated government). It would have been politically easy for then-Mayor Goldsmith to coast and show no courage in attacking government reform.

Considering that’s what he did without serious motivating factors, it says volumes about the seriousness and focus that we need in Memphis, considering city government’s budgetary exigencies and the deep needs in our city. Based on Mayor Wharton’s comments, we suspect that sanitation is only the first step in reimagining how city services can be provided.

For Mayor Goldsmith, it began with an articulate vision of what he wanted Indianapolis to be: A competitive city with safe streets, strong neighborhood and a thriving economy.” Here, Mayor Wharton has announced his vision for Memphis as a city of choice: Middle income families live here, public school students have options for the future, poor families move into the economic mainstream, and talented workers are developed, attracted and retained.

Better Government

Mr. Goldsmith’s core tenets:

Government should be a rudder, not an engine.

People know better than government and what is in their best interest.

Government should be measured the same way every other enterprise is measured: by its results.

Government works in collaboration, not in isolation.

Government should do no harm.

Liberating Employees

After performing a different city job each month, Mr. Goldsmith decided that most employees were competent but trapped in systems that ill-served them – or the public. To stimulate new thinking, he said up incentive pay for people who saved money and merit pay so employees’ raises were based on their performance. In the end, productivity climbed as the size of the workforce lowered.

Mayor Wharton is emphatic about one thing: The business model for local government is broken. It’s hard to find anyone in the public who would argue with him, and if Memphis and Mayor Wharton are to find inspiration for better government and new ideas, managed competition is a great place to start.

Most of all, it’s encouraging that after a 25-year absence, Memphis is getting attention, advice and solutions from national experts. To borrow a phrase from Mr. Goldsmith, there’s nothing more exciting than the “politics of the possible.”

I have to say, when I read the article on Sunday I knew that SCM would be grinning ear to ear as I am. Mayor Wharton’s biggest challenges will be educating the unions and the public concerning the details and the benefits of such an approach. One note of resistance in the CA article illustrated some of the difficulties that might be encountered in such a transition. The idea voiced by the union spokesperson stated that any layoffs within the ranks of the sanitation department would be viewed as a drawback to the plan. The simple fact is that the sanitation workers would be in control of such measures and will no doubt relate to the profitability and efficiency that they would deem possible. It reeks of the type of entitlement that can no doubt be found throughout such public departments both locally and nationally. One of the messages from City Hall, should the program proceed, is that the city does not exist to create these positions and provide employment. Rather these positions exist to serve the city and its citizens.

The end result will be beneficial for both the sanitation workers and the public.