It is little news to anyone familiar with the Memphis market that property along the Poplar corridor is by far the most reliable real estate investment in the region. Generally speaking, the closer a particular property is to Poplar Avenue, the higher its valuation and the greater its annual appreciation.

It is little news to anyone familiar with the Memphis market that property along the Poplar corridor is by far the most reliable real estate investment in the region. Generally speaking, the closer a particular property is to Poplar Avenue, the higher its valuation and the greater its annual appreciation.

This is not only true for retail, where a Poplar address can provide a landlord some of the highest occupancy rates in the city, but also for office and residential uses, as well. If you were to place the locations of Class A office space on a map, you would find a cluster downtown, a few in the medical district and a long, linear pattern along Poplar stretching from Perkins Ext. to Kirby. Since executives prefer to live close to where they work, the Class A office space downtown and the medical district helps buoy the Harbor Town, downtown, Evergreen and Central Gardens home appraisals, while the Perkins-to-Kirby Class A office space helps buoy everything from Chickasaw Gardens on out to Piperton.

With the supremacy of the Poplar corridor, where does that leave the rest of the Memphis metropolitan area that is not within close proximity to good old State Route 57?

History

History shows us that developments that are too far-flung from Poplar have not been the epitome of success.

One of the earliest residential examples of this phenomenon is the Kerr Avenue Subdivision (the neighborhood around Marjorie Street), platted way back in 1891. Despite the fact that the subdivision featured the first curvilinear streets in the city, the subdivision remained essentially vacant for nearly 20 years and was not substantially built out until the 1930s.

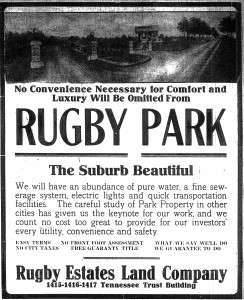

A similar fate befell the Rugby Subdivision in Frayser (the neighborhood along Overton Crossing). It was platted in 1910, and despite heavy advertising and similarly bucolic design as the Kerr Ave. Sub’d., it took some forty years to be substantially complete. Once these two subdivisions were finally finished, their home values did not necessarily take off.

Winners and Losers

These neighborhoods may represent the extreme, but even subdivisions that had the benefit of being completed in relatively short order have been subject of being forgotten by the market. Today, we see large swaths of the region go from brand new to bad and then to worse within a matter of a few years. While every city has their areas that appreciate in property values more than others, it seems that metropolitan Memphis has more than its fair share of failing neighborhoods.

So, with our very few winners who own and rent along Poplar, we have many, many more losers who are not so lucky. So, how do we help the losers?

One possible solution is to address the mismatch between supply and demand in the Memphis market. We currently have far too many houses and storefronts for a region that is attracting fewer and fewer folks from other areas. Nothing short of a regional land use authority (I’ll discuss that in a subsequent post) can be done about Tipton, DeSoto and Fayette Counties’ propensity to approve each and every subdivision and shopping center that comes across their desks for approval.

2 + 2 = 0

Likewise, the suburban cities within Shelby County will continue to attend to their own economic needs by approving developments within their borders. After all, under our current tax structure, all municipalities are engaged in a highly competitive, zero-sum game to increase and sustain their individual tax bases.

With that said, Memphis-Shelby County still has land use control over large undeveloped tracts, especially in the area east of Houston Levee between the Wolf River and US 64. While not quite as hot as the Poplar Corridor, the Walnut Grove/Cordova Corridor is arguably second in holding its values. By adhering to the imminent uniform development code and other land use plans approved for that area and resisting the urge to approve sprawling new developments, some of the overdevelopment in the region will cease, and maybe – just maybe – demand will catch up to supply and the Poplar corridor will be joined by other successful corridors throughout our city and region.

In my next post: What about the argument that turning down developments in the Walnut Grove/Cordova corridor will just move that growth to Fayette County?

Hi Josh! Your old bus pal here. Glad to see you are blogging on one of my fave sites! I’m actually trying to track down Tom. Is he still blogging here? Looking forward to reading more posts!

Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon.

Thanks for taking the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love learning more on this topic. If possible, as you gain expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more information? It is extremely helpful for me.

Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon.

Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon.